IRS Offers Expatriate Tax Deal – Expatriate Now!

In this post, I’ll look at the 2020 IRS offers to low and medium-income expatriates – US citizens that wish to give up their US passports and escape the IRS once and for all. This expatriate tax deal is very limited in scope. But, if you qualify, you should act now to expatriate!

Editor’s Note: This section applies to those who have given up their US citizenship or those who plan to give up their US citizenship. This tax offer is made to persons who expatriate from the United States.

I mention this because, the term “expat,” commonly referrers to US persons living outside of the United States. Here, the term expatriate means someone who has gone through the process of renouncing his or her US citizenship.

With that said, here’s the 2020 IRS offer to expatriates:

Certain individuals who expatriate from the United States may be able to avoid the exit tax and other outstanding tax liabilities using the procedures the IRS recently outlined its website and announced in News Release IR-2019-151.

This tax deal applies to individuals who gave up or will give up their U.S. citizenship after March 18, 2010, and meet a number of other criteria listed below. Native-born or naturalized U.S. citizens generally may voluntarily relinquish their citizenship for reasons and under procedures listed at 8 U.S.C. Section 1481(a).

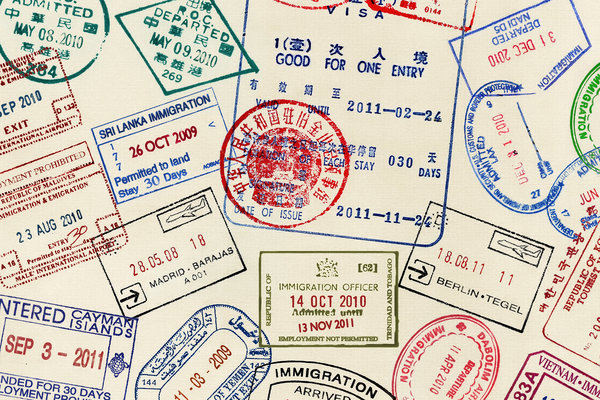

In most cases, this means that make an appointment at a US consulate and formally renounce your US citizenship. You must also turn in your passport.

This means that you must have a second passport in hand before you give up your US citizenship. It’s impossible to become “stateless.’ While this may seem obvious, you’d be surprised how many calls I get regarding expatriation from people who do not yet have a second passport and second citizenship.

Per the US tax code, expatriates must comply with all federal tax requirements for the year of expatriation and for the five immediately prior tax years. In addition, Sec. 877A imposes a tax on “covered expatriates” that deems most property as sold for its fair market value on the day before the day of expatriation. If the net gain is over $725,000 (for 2019), the gain over this amount is includible in income for tax year 2019 (the 2020 number is not available at the time of this writing).

A covered expatriate is anyone who:

- Has an average annual net income tax liability in the five tax years ending before the date of expatriation of more than a specified amount ($168,000 for 2019);

- Has a net worth of $2 million or more; or

- Cannot certify under penalty of perjury that he or she has met all applicable tax requirements for the five preceding tax years or fails to submit evidence of compliance the IRS may require. This certification can be made with Form 8854, Initial and Annual Expatriation Statement.

That is to say, you’re a covered expatriate regardless of your net worth and income if you cannot make the certification. In my experience, individuals who have not filed their returns, or go through the expatriation process without the assistance of a tax expert, become covered individuals under #3.

That is to say, there is no requirement to be in compliance with your US tax obligations before you give up your citizenship. So long as you have a second passport, you can make an appointment and give up your US passport.

However, if you do this without first satisfying your IRS obligations, you become a “covered person’ by default. This tax liability will follow you into your new life. Unless and until you go through the formal process, you will never be free of the IRS.

Also, international banks will only consider you a non-US person after you go through the formal process and receive a Certificate of Loss of Nationality from a US Embassy. This letter, which costs $2,350, must be provided to your international bank to remove your account(s) from their FATCA reporting systems.

That is to say until you receive a Certificate of Loss of Nationality, banks will consider you a US citizen and report your accounts to the IRS under FATCA.

Under the new deal for expatriates, individuals who meet the requirements will not be considered covered expatriates and will not be liable for any unpaid taxes and penalties for the year of expatriation and previously. As stated above, the expatriation must have occurred after March 18, 2010.

Also, for the six tax years at issue (the year of expatriation and the five immediately prior years), any failure to file required tax returns and pay taxes and penalties for the years at issue must have been due to the taxpayer’s nonwillful conduct.

Required tax returns include income, gift, and information returns (the latter including Form 8938, Statement of Specified Foreign Financial Assets), and FinCEN Form 114, Report of Foreign Bank and Financial Accounts, commonly known as FBAR. Nonwillful conduct is that which is due to negligence, inadvertence, mistake, or a good-faith misunderstanding of legal requirements.

In addition, to be eligible for relief, the individual must:

- Have no filing history as a U.S. citizen or resident (not including Form 1040NR, U.S. Nonresident Alien Income Tax Return, under a good-faith but mistaken belief that the individual was not a U.S. citizen);

- Meet the above income tax liability limits for covered expatriates for the period of five tax years ending before the date of expatriation and meet the $2 million-net-worth limit at the time of expatriation and when applying for the relief;

- Have an aggregate US tax liability of no more than $25,000 for the six tax years at issue (after application of all applicable deductions, exclusions, exemptions, and credits, including foreign tax credit and foreign earned income exclusion, but excluding penalties, interest, and the exit tax of Sec. 877A); and

- Agree to complete and submit all required federal tax returns for the six tax years at issue, including all required schedules and information returns.

The bottom line is that this tax deal for expatriates is meant for those who have lived their entire adult lives outside of the United States and have never filed a US 1040 personal income tax return. The most common example would be someone who has grown up in the UK, has a US passport because his father was a US citizen, has never lived in the US (though, they may have visited), and was unaware of their US tax filing obligations.

Also, this expatriate tax offer is for lower to middle-income individuals. You must have a net worth of less than $2 million in the year you give up your US citizenship. I guess the IRS figures it’s not cost-effective to chase down those with a net worth of less than $2 million.

Finally, your net US tax due must be less than $25,000 per year. This will depend more on where you live than your net income. Because of the foreign tax credit, someone living in a high tax country such as France, and making $5 million a year, might owe nothing to the IRS when they file their US returns. Conversely, someone living in a zero-tax country, such as Belize, might owe more than $25,000 to the IRS on a salary of $200,000.

If you meet the qualifications above, and you’re thinking about giving up your US citizenship, now is the time to do it. You should file and renounce during 2020 while the program is still in effect.