The IRS Offshore Voluntary Disclosure Program for 2017 offers taxpayers with undisclosed offshore accounts the ability to come forward voluntarily, file their returns, disclose their assets, pay the resulting taxes and penalties, and receive a clean slate. This article covers amendments to the Offshore Voluntary Disclosure Program through February 9, 2017.

As of 2017, the IRS Offshore Voluntary Disclosure Program has collected about $8 billion in taxes and penalties from US persons with undisclosed offshore accounts. The last official number reported by the Service was $6.5 billion taken from 45,000 taxpayers as of June 2014. Unofficial estimates put it at $8 billion today.

The OVDP first came out in 2009 when the IRS was putting pressure on the Swiss bank UBS to turn over account records of US citizens. The IRS claimed that UBS was illegally helping US citizens to hide money from the tax man.

When the dust settled, UBS bowed to the US government. The bank agreed on February 18, 2009 to pay a fine of US$780 million to the U.S. government. This ransom payment broke the back of Swiss privacy and lead to the situation we have today where US persons have zero right to privacy in their financial dealings.

The IRS Offshore Voluntary Disclosure Program allows taxpayers with undisclosed accounts to avoid criminal prosecution and to “come into the fold” as it were. The OVDP is designed for US persons who voluntarily report their foreign accounts and avoid the draconian penalties the IRS will impose if they catch you.

- A “US person” is any US citizen, green card holder, and resident of the US. The definition can include anyone who spends more than 183 days a year in the US and doesn’t usually include non-resident aliens, but exceptions apply.

- For a detailed list of penalties and charges you can face if you’re caught with an offshore account, and don’t voluntarily come forward, see FAQs 5 and 6 here.

Before I get into the terms of the IRS Offshore Voluntary Disclosure Program for 2017, note that this program is sometimes referred to the 2012 OVDP or 2014 OVDI. The last major changes to the program came in July 1, 2014. There have been several comments and clarifications from that date to February 9, 2017. This article was written in May of 2017.

The following applies to US persons with undisclosed foreign bank accounts. You were required to report any bank or brokerage account(s) outside of the US with more than $10,000.

This is the combined balance of all your foreign accounts. For example, if you had $6,000 in an account in France and $6,000 in an account in Switzerland, your combined balance was $12,000 and you had a filing obligation.

This filing requirement is based on the highest balance in the foreign account for any one day of the year. It’s not your average balance during the year or year-end balance.

Let’s say you were buying an apartment in Belize for $200,000 in 2015. You opened a bank account on the island and transferred the purchase money to that account. One day later you wired the $200,000 out of your Belize account and into an escrow account. You had a reporting requirement for 2015 because you had more than $10,000 offshore for that one day.

If you’d sent the money directly from a US account into an escrow account, you would not have a US reporting obligation. This is because an escrow account is not in your name and not under your control.

That is to say, you are required to report any offshore account in your name or under your control. Having a nominee on the account doesn’t eliminate the filing requirement because you still maintain control.

The focus of the IRS Offshore Voluntary Disclosure Program has been offshore bank accounts. There are many other filing deficiencies can be cured through the OVDP. For example, you should be filing Form 5471 if you hold shares in an offshore company. Then there’s Forms 3520 and 3520-A for foreign trust and Form 8938, Statement of Foreign Financial Assets.

Bottom line, if you had an interest in a foreign bank account or structure, you probably had a US filing requirement and should consider the IRS OVDP.

IRS Offshore Voluntary Disclosure Program for 2017 Settlement Terms

There are two flavors of the IRS OVDP, the Streamlined Offshore Voluntary Disclosure Program and the Traditional Offshore Voluntary Disclosure Program. Clients with a low risk of criminal prosecution, and a valid cause for their failure to report and pay, will usually select the streamline option.

Those who are coming forward after their foreign bank entered into an agreement with the IRS, or who’se financial advisor made a deal to turn over their client list, will need to go with the more expensive traditional program. Likewise, those with no valid cause for the account, or who took steps to hide the account from the IRS, should go with the traditional program.

Traditional Offshore Voluntary Disclosure Program

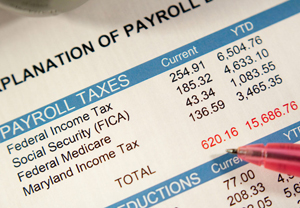

The penalties under the traditional OVDP are as follows:

- A 20-percent accuracy-related penalty on the tax due with the filing of your amended returns for all years. If no tax is due with the filing, then no accuracy penalty will apply;

- Pay failure-to-file and failure-to-pay penalties, if applicable; and

- Pay, in lieu of all other penalties 27.5% of the highest aggregate value of your foreign assets during the period covered by the voluntary disclosure.

If your bank is under investigation, a 50% penalty might apply rather than the 27.5% above. Remember that the purpose of the program is to convince Americans to come forward voluntarily. If the IRS believes they’d have caught you eventually without the disclosure, they’re going to hit you hard.

The 27.5% penalty applies to all foreign assets which you failed to disclose. If all you had offshore was a bank account, the penalty is based on the highest value of the account during the OVDI period.

In my example above, a client had an offshore bank account that held $200,000 for only one day. In that case, the standard OVDI penalty is 27.5% of $200,000, or $55,000.

If you have other reportable assets, such as foreign real estate, an offshore trust, and a brokerage account, the penalty can apply to the highest value of these assets combined plus the highest value of your offshore bank account.

The OVDP penalty is often assessed on the highest value from a few years back because that’s when you were making money offshore. Since that high-water mark, the brokerage account may lost money, the bank accounts depleted, and the real estate has gone to foreclosure… I even had a client that had all his money stolen by an offshore scammer. None of these losses matter. The penalty is on the highest value and later losses are disregarded.

See FAQ 8 and 31 through 41 on the IRS website for more details on how to calculate the standard penalty.

Streamlined Offshore Voluntary Disclosure Program

The streamlined filing compliance program is available to those who can certify that their failure to report foreign financial assets and pay all tax due in respect of those assets did not result from willful conduct on their part. You must state, and should be able to prove, that you didn’t intend to use the offshore account to avoid paying your taxes.

That is to say, you must state under penalty of perjury that your conduct was not willful. That the failure to report all income, pay all tax and submit all required information returns, including FBARs was due to non-willful conduct.

Non-willful conduct is conduct that is due to negligence, inadvertence, or mistake or conduct that is the result of a good faith misunderstanding of the requirements of the law.

The risk with the streamlined program is that the IRS doesn’t buy your claim of non-willfulness. If they have evidence that you intended to hide money from the Service, or that you lied on the streamlined application, they will come after you with guns blazing.

The reduced penalties under the streamlined OVDP are as follows:

For US persons living in the United States:

- File original or amended tax returns, together with all required information returns (e.g., Forms 3520, 3520-A, 5471, 5472, 8938, 926, and 8621) for the last years properly reporting your offshore accounts, assets, and income,

- File original or amended FBARs for the last 6 years, and

- Pay the tax, interest, and a miscellaneous 5% penalty with the filing of your OVIP.

The streamlined penalty for US residents is equal to 5% of the highest aggregate balance/value of your reportable foreign financial assets. For this purpose, the highest aggregate balance/value is the highest year-end balance… which might not be the highest balance for the year.

In our example above, you had $200,000 in an offshore account for one day. Assuming that wasn’t December 31, you’re streamlined penalty won’t include that deposit.

A foreign financial asset is any asset that should have been reported on the FBAR (FinCEN Form 114) or Form 8938. The most common examples of foreign financial assets include:

- Bank and brokerage accounts held at foreign financial institutions;

- Bank and brokerage accounts held at a foreign branch of a U.S. financial institution;

- foreign stock or securities not held in a financial account;

- foreign mutual funds; and

- foreign hedge funds and foreign private equity funds.

Note that the streamlined OVDP penalty applies to foreign financial assets while the traditional OVDP applies to all foreign assets.

If you’re eligible for the Streamlined Domestic Offshore Voluntary Disclosure Program, you can avoid accuracy-related penalties, information return penalties, and FBAR penalties. In most cases, the 5% miscellaneous penalty will be the only penalty assessed.

For US persons living abroad:

If both you and your spouse are non-residents for US tax purposes, you might be eligible for the zero penalty version of the streamlined program. If you’re living abroad, and otherwise qualify for the Streamlined Foreign Offshore Voluntary Disclosure Program, the IRS will allow you to file or amend your returns without the 5% penalty.

Keep in mind that your failure to file or pay taxes must have been non-willful. This criteria is the same for both domestic and foreign filers.

You’re a US citizen “living abroad” for the streamlined OVDP if you were out of the United States for 330 days for one of the last three tax years. If you’re OVDP filing covers tax years 2014, 2015 and 2016 (it is now 2017), then you must have been out of the country for 330 days during one of those years.

If you qualify for the foreign streamlined OVDP, you must submit your last 3 years of returns, 6 years of FBARs, and pay any tax and interest at the time of filing.

The purpose of the foreign streamlined program is to allow American’s living abroad to get back into the system without a penalty. The IRS has determined that, on balance, US persons who are out of the US for 330 days, and thus have few ties to this country, are the most innocent when it comes to their failure to file and pay taxes.

And, when you take the Foreign Earned Income Exclusion and the Foreign Tax Credit into account, most American’s living abroad pay little or no US taxes on their income. In that case, you will pay little to nothing with your foreign streamlined OVDP.

A US citizen who is a resident of a foreign country, or is out of the US for 330 days during any 365 day period, qualifies for the Foreign Earned Income Exclusion. The FEIE allows you to earn about $100,000 in salary or business income free of Federal income taxes. For more on the FEIE, see: Foreign Earned Income Exclusion for 2017

You also get to deduct any foreign taxes paid on your US returns, even when those returns are filed as part of an OVDP. You essentially get a dollar for dollar credit against any taxes paid on your US return.

So, if you’re living in a country with a tax rate equal to or higher than the United States, you shouldn’t owe any US tax on your foreign income. In that case, you’ll pay nothing with your foreign streamlined OVDP.

If you’re living in a zero or no tax country, or aren’t required to pay local tax to your country of residence, then you’ll pay some US tax with your OVDP. If your salary exceeded the FEIE, you will owe US tax on the excess. If you have capital gains, they’ll will be taxable when you file or amend your US returns.

Conclusion

The IRS Offshore Voluntary Disclosure Program for 2017 allows US persons to come out from the cold and get back into the good graces of the US government. No matter the reason for your failure to file, and I’ve heard them all, the OVDP is your best path forward

I hope you’ve found this article on the OVDP for 2017 to be helpful. For more information, please contact us at info@premieroffshore.com or call (619) 483-1708. We’ll be happy to assist you to file a streamlined or traditional Offshore Voluntary Disclosure and negotiate the best settlement available.