An offshore trust owned by a U.S. person must file Form 3520-A and a variety of other reports to remain in compliance with the IRS. Here are the tax filing requirements for offshore trusts with U.S. owners.

First, allow me to define a few terms around offshore trust tax reporting:

Settlor or Grantor: The person or persons creating and funding the trust. The terms settlor and grantor are synonyms for estate planning and the U.S. tax code.

Owner of an Offshore Trust: The settlor is the owner of the trust until his death. Once the trust passes to the heirs, they become the owners for U.S. tax purposes.

Grantor Trust: A grantor trust is considered a disregarded entity for income tax purposes. Any taxable income or deduction earned by the trust will be taxed on the grantor’s tax return. The settlor(s) or grantor(s) are the beneficial owner of the trust for tax purposes until his or her death.

Beneficial Owner: The owner of the assets of the trust for tax purposes. More specifically, Any person treated as an owner of any portion of a foreign trust under the grantor trust rules (Sections 671 to 679 of the U.S. Tax Code).

U.S. Person: Any U.S. citizen, green card holder, or tax resident. This article is focused on offshore trusts owned by U.S. persons. The rules are different for offshore trusts owned by non-resident aliens who become U.S. persons after the trust is funded.

Tax Resident: Any person who spends more than 183 days a year in the United States.

Now let’s get to the U.S. tax filing requirements of offshore trusts with U.S. owners.

We start from the position that U.S. persons are taxed on their worldwide income, no matter where it’s earned and no matter where they live. So long as you hold a U.S. passport or green card, or are a U.S. resident for tax purposes, the IRS will expect you send them their share each year.

Next, all offshore trusts with U.S. owners are grantor trusts for U.S. tax purposes. This means that all income earned within an offshore trust is taxable to the grantor. Likewise, this means that the settlor is considered the beneficial owner of the trust assets for tax purposes.

Note that I repeatedly write, “for tax purposes.” The settlor may not be considered the owner of the assets for liability and litigation purposes. Also, she might not be the owner of the assets for estate planning purposes. This article on the U.S. tax status and filing requirements of offshore trusts looks at these matters only from the point of view of the IRS.

This all means that the settlor or owner of an offshore trust must pay U.S. tax on the taxable gains earned within the trust. This includes capital gains from stock trading, rental income from real estate, and the gain realized on the sale of any trust assets.

Of course, it’s possible for an offshore trust to have non-taxable gains. For example, profits earned within a U.S. compliant offshore insurance wrapper are not taxable to the owner.

The bottom line is that, any income earned within an offshore trust which is not within a tax exempt structure is taxable to the owner. Taxes are not deferred until the profits are brought into the United States, they’re due when the gains are realized.

U.S. Tax Filing Requirements for Offshore Trusts

The most important filing requirement for an offshore trust with a U.S. owner is Form 3520-A.

An offshore trust treated as a grantor trust for U.S. tax purposes must file IRS Form 3520-A each year. Gains, losses and ownership are reported to the IRS on this form. It doesn’t matter whether there were transactions or gains in the trust, Form 3520-A must be filed each and every year.

Failure to file Form 3520-A, or filing an incomplete or inaccurate Form 3520-A can result in a penalty of the greater of $10,000 per year or 5% of the gross value of the trust assets owned by U.S. persons. That means that the minimum penalty for failing to file this form is $10,000 per year.

An offshore trust where the settlor is alive and a U.S. person will be 100% owned by a U.S. person and the penalty for failing to file Form 3520-A will be 5% of 100% of the trust assets. In the situation where the settlor has passed and one or more of the beneficiaries are not U.S. persons, the penalty will apply only to the portion of the assets owned by U.S. persons.

Note that an offshore trust with U.S. owners must also file Form 3520 to report changes in ownership and certain transactions involving the trust. Failure to file this subform will result in an additional penalty of the greater of $10,000 per year or 5% of the gross value of the trust assets owned by U.S. persons.

So, failure to report an offshore trust in a year where both Form 3520-A and Form 3520 are required can result in a total penalty of $20,000 or 10% of the gross assets. Miss these forms or file them incorrectly for a few years and the penalties add up quickly.

Foreign Bank Account Report (FBAR)

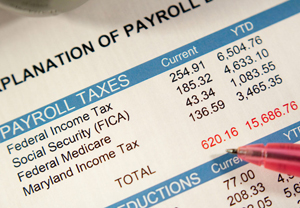

The most basic offshore form is the Report of Foreign Bank and Financial Accounts, Form FinCEN 114, generally referred to as the FBAR. Anyone who is a signor or beneficial owner of a foreign bank or brokerage account with a value of more than $10,000 must disclose their account(s) to the U.S. Treasury.

The $10,000 amount is the value of all offshore bank and brokerage accounts combined. If you have 4 offshore accounts, each with $4,000, your total offshore balance is $16,000 and an FBAR report is due each year.

The penalty for failing to disclose an offshore bank account is $10,000 for each non-willful violation. If the violation is intentional, the penalty is the greater of $100,000 or 50% of the amount in the account for each violation. A separate penalty will be imposed for each year you failed to report the international bank and/or brokerage account associated with your offshore trust.

In addition to filing the Foreign Bank Account Report, your offshore account must be disclosed on Form 1040, Schedule B of your personal tax return.

Other Tax Forms for Offshore Trusts

Form 5471 – Information Return of U.S. Persons with Respect to Certain Foreign Corporations. If your trust owns a foreign corporation, Form 5471 will be required.

A foreign corporation or limited liability company owned by an offshore trust should review the default classifications in Form 8832, Entity Classification Election and decide whether to make an election to be treated as a corporation, partnership, or disregarded entity.

Form 8858 – Information Return of U.S. Persons with Respect to Foreign Disregarded Entities. If your foreign trust owns an offshore Limited Liability Company, you might need to file Form 8858. If not this form, then Form 5471. Which form is required is determined using the instructions to Form 8832.

Form 5472 – Information Return of a 25% Foreign-Owned U.S. Corporation. If your offshore trust invests in a U.S. business, or in an offshore corporation that does business in the United States, you may need to file Form 5472 to report U.S. source income.

Form 926 – Return by a U.S. Transferor of Property to a Foreign Corporation. Form 3520 is generally used to report transfers to an offshore trust. Form 926 can be required if you transfer property into a foreign corporation owned by your trust.

Form 8938 – Statement of Foreign Financial Assets was introduced in 2011 and must be filed by anyone with significant assets outside of the United States. Whether this Form 8938 is required will depend on many factors, such as the value of your foreign assets and whether you’re living in the United States or abroad. I won’t go into the details here. Suffice it to say that most offshore trusts are large enough that Form 8938 is required.

Conclusion

Because of the complex web of tax forms and rules that apply to offshore trusts, the severe penalties for getting it wrong, and the potential to use an offshore trust as a tax planning tool (when combined with an insurance wrapper) or as a way to minimize estate tax, I strongly suggest you hire a U.S. expert to form your structure.

Only a U.S. tax and asset protection lawyer is qualified to design and implement an offshore trust for an American citizen or resident.

Only a professional with years of experience in the field should be hired to quarterback your asset protection team.

Only a U.S. lawyer can build an asset protection trust to protect you from U.S. creditors. If your risks are in the United States, so must be your legal counsel.

Only a U.S. tax expert is qualified to keep your offshore trust in compliance.

Only an attorney experienced in both offshore planning and U.S. taxation can assist you with pre-immigration planning using offshore trusts.

Sure, it’s cheaper to hire an offshore trust agent. Take a read through the penalties for failure to file or report again, and then consider whether the savings are worth the risk.

Here’s the bottom line: If you can’t afford to do it right, don’t do it at all. If the amount of assets you want to transfer offshore don’t warrant hiring a U.S. lawyer, then don’t go with a trust. Plant your first flags offshore in a less costly and less complex structure.

For example, if you will move $100,000 offshore, go with a Panama Foundation rather than an offshore trust. The cost savings will be significant and the Foundation offers many of the same asset protection benefits. Also, a Panama Foundation is a great way to hold active trading accounts and businesses, which don’t play well with offshore trusts.

If you want to take a U.S. retirement account offshore, use an offshore IRA LLC rather than an international trust. Your setup and ongoing costs will be a small fraction of those associated with a properly designed trust.

Finally, it’s possible to invest offshore and legally report nothing to the IRS. If you buy foreign real estate, or hold gold offshore in your name, there will be no IRS reports to file. Stick to gold and real estate, avoid offshore structures, and do not have an offshore bank accounts with more than $10,000, and your investments will remain totally private.

Assets within an offshore corporation, including gold and real estate, must be reported on Form 5471. The above refers only to assets held in your name without a corporate structure, LLC, or foreign trust. For more, see: Offshore Privacy Exists!

I hope you’ve found this article on the U.S. tax status and IRS filing obligations of offshore trusts to be helpful. For more information on building an international asset protection structure, please contact me at info@premieroffshore.com or call us at (619) 483-1708 for a confidential consultation.